Paul Dirac

| Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac | |

|---|---|

| Born | Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac 8 August 1902 Bristol, England |

| Died | 20 October 1984 (aged 82) Tallahassee, Florida, USA |

| Nationality | Switzerland (1902–19) United Kingdom (1919–84) |

| Fields | Physics (theoretical) |

| Institutions | University of Cambridge Florida State University |

| Alma mater | University of Bristol University of Cambridge |

| Doctoral advisor | Ralph Fowler |

| Doctoral students | Homi Bhabha Harish Chandra Mehta Dennis Sciama Fred Hoyle Behram Kurşunoğlu John Polkinghorne |

| Known for | Dirac equation Dirac comb Dirac delta function Fermi–Dirac statistics Dirac sea Dirac spinor Dirac measure Bra-ket notation Dirac adjoint Dirac large numbers hypothesis Dirac fermion Dirac string Dirac algebra Dirac operator Abraham-Lorentz-Dirac force Dirac bracket Fermi–Dirac integral Negative probability Dirac Picture Dirac-Coulomb-Breit Equation |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Physics (1933) Copley Medal (1952) Max Planck Medal (1952) |

|

Notes

He is the stepfather of Gabriel Andrew Dirac. |

|

| Quantum mechanics |

|---|

|

| Introduction Glossary · History |

|

Background

|

|

Fundamental concepts

|

|

Formulations

|

|

Equations

|

|

Advanced topics

|

|

Scientists

Bell · Bohm · Bohr · Born · Bose

de Broglie · Dirac · Ehrenfest Everett · Feynman · Heisenberg Jordan · Kramers · von Neumann Pauli · Planck · Schrödinger Sommerfeld · Wien · Wigner |

Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac OM, FRS ( /dɪˈræk/ di-rak; 8 August 1902 – 20 October 1984) was an English theoretical physicist who made fundamental contributions to the early development of both quantum mechanics and quantum electrodynamics. He held the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge and spent the last fourteen years of his life at Florida State University.

Among other discoveries, he formulated the Dirac equation, which describes the behaviour of fermions, and predicted the existence of antimatter.

Dirac shared the Nobel Prize in physics for 1933 with Erwin Schrödinger, "for the discovery of new productive forms of atomic theory."[1]

Contents |

Early years

Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac was born at his parents' home in Bristol, England on 8 August 1902,[2] and grew up in the Bishopston area of the city.[3] His father, Charles Adrien Ladislas Dirac, was an immigrant from Saint-Maurice in the Canton of Valais, Switzerland, who worked in Bristol as a French teacher. His mother, Florence Hannah Dirac, née Holten, the daughter of a ship's captain, worked as a librarian at the Bristol Central Library. Paul had a younger sister, Béatrice Isabelle Marguerite, known as Betty, and an older brother, Reginald Charles Félix, known as Felix,[4][5] who committed suicide in March 1925.[6] Dirac later recalled: "My parents were terribly distressed. I didn't know they cared so much. ...I never knew that parents were supposed to care for their children, but from then on I knew."[7]

Charles and the children were officially Swiss nationals until they became naturalised on 22 October 1919.[8] Dirac's father was strict and authoritarian, although he disapproved of corporal punishment.[9] Dirac had a strained relationship with his father, so much so that after his death, he wrote, "I feel much freer now, and I am my own man." Charles forced his children to speak to him only in French, in order that they learn the language. When Dirac found that he could not express what he wanted to say in French, he chose to remain silent.[10][11]

Dirac was educated first at Bishop Road Primary School[12] and then at the all-boys Merchant Venturers' Technical College (later Cotham School), where his father was a French teacher.[13] The school was an institution attached to the University of Bristol, which shared grounds and staff.[14] It emphasised technical subjects like bricklaying, shoemaking and metal work, and modern languages.[15] This was an unusual arrangement at a time when secondary education in Britain was still dedicated largely to the classics, and something for which Dirac would later express gratitude.[14]

Dirac studied electrical engineering on a City of Bristol University Scholarship at the University of Bristol's engineering faculty, which was co-located with the Merchant Venturers' Technical College.[16] Shortly before he completed his degree in 1921, he sat the entrance examination for St John's College, Cambridge. He passed, and was awarded a £70 scholarship, but this fell short of the amount of money required to live and study at Cambridge. Despite graduating with a first class honours bachelor of science degree in engineering, the economic climate of the post-war depression was such that he was unable to find work as an engineer. Instead he took up an offer to study for bachelor of arts degree in mathematics at the University of Bristol free of charge. He was permitted to skip the first year of the course owing to his engineering degree.[17]

In 1923, Dirac graduated, once again with first class honours, and received a £140 scholarship from the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research. Along with his £70 scholarship from St John's College, this was enough to live at Cambridge. There, Dirac pursued his interests in the theory of general relativity, an interest he gained earlier as a student in Bristol, and in the nascent field of quantum physics, under the supervision of Ralph Fowler.[18]

Career

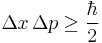

Dirac noticed an analogy between the Poisson brackets of classical mechanics and the recently proposed quantization rules in Werner Heisenberg's matrix formulation of quantum mechanics. This observation allowed Dirac to obtain the quantization rules in a novel and more illuminating manner. For this work, published in 1926, he received a Ph.D. from Cambridge.

In 1928, building on 2x2 spin matrices which he discovered independently (Abraham Pais quoted Dirac as saying "I believe I got these (matrices) independently of Pauli and possibly Pauli got these independently of me")[19] of Wolfgang Pauli's work on non-relativistic spin systems, he proposed the Dirac equation as a relativistic equation of motion for the wavefunction of the electron.[20] This work led Dirac to predict the existence of the positron, the electron's antiparticle, which he interpreted in terms of what came to be called the Dirac sea.[21] The positron was observed by Carl Anderson in 1932. Dirac's equation also contributed to explaining the origin of quantum spin as a relativistic phenomenon.

The necessity of fermions (matter being created and destroyed in Enrico Fermi's 1934 theory of beta decay), however, led to a reinterpretation of Dirac's equation as a "classical" field equation for any point particle of spin ħ/2, itself subject to quantization conditions involving anti-commutators. Thus reinterpreted, in 1934 by Werner Heisenberg, as a (quantum) field equation accurately describing all elementary matter particles- today quarks and leptons – this Dirac field equation is as central to theoretical physics as the Maxwell, Yang-Mills and Einstein field equations. Dirac is regarded as the founder of quantum electrodynamics, being the first to use that term. He also introduced the idea of vacuum polarization in the early 1930s. This work was key to the development of quantum mechanics by the next generation of theorists, and in particular Schwinger, Feynman, Sin-Itiro Tomonaga and Dyson in their formulation of quantum electrodynamics.

Dirac's Principles of Quantum Mechanics, published in 1930, is a landmark in the history of science. It quickly became one of the standard textbooks on the subject and is still used today. In that book, Dirac incorporated the previous work of Werner Heisenberg on matrix mechanics and of Erwin Schrödinger on wave mechanics into a single mathematical formalism that associates measurable quantities to operators acting on the Hilbert space of vectors that describe the state of a physical system. The book also introduced the delta function. Following his 1939 article,[22] he also included the bra-ket notation in the third edition of his book,[23] thereby contributing to its universal use nowadays.

In 1933, following his 1931 paper on magnetic monopoles, Dirac showed that the existence of a single magnetic monopole in the universe would suffice to explain the observed quantization of electrical charge. In 1975,[24] 1982,[25] and 2009[26][27][28] intriguing results suggested the possible detection of magnetic monopoles, but there is, to date, no direct evidence for their existence.

Dirac was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge from 1932 to 1969. In 1937, he proposed a speculative cosmological model based on the so-called large numbers hypothesis. During World War II, he conducted important theoretical and experimental research on uranium enrichment by gas centrifuge.

Dirac's quantum electrodynamics made predictions that were – more often than not – infinite and therefore unacceptable. A workaround known as renormalization was developed, but Dirac never accepted this. "I must say that I am very dissatisfied with the situation," he said in 1975, "because this so-called 'good theory' does involve neglecting infinities which appear in its equations, neglecting them in an arbitrary way. This is just not sensible mathematics. Sensible mathematics involves neglecting a quantity when it is small – not neglecting it just because it is infinitely great and you do not want it!"[29] His refusal to accept renormalization resulted in his work on the subject moving increasingly out of the mainstream. However, from his once rejected notes he managed to work on putting quantum electrodynamics on "logical foundations" based on Hamiltonian formalism that he formulated. He found a rather novel way of deriving the anomalous magnetic moment "Schwinger term" and also the Lamb shift, afresh, using the Heisenberg picture and without using the joining method used by Weisskopf and French, the two pioneers of modern QED, Schwinger and Feynman, in 1963. That was two years before the Tomonaga-Schwinger-Feynman QED was given formal recognition by an award of the Nobel Prize for physics. Weisskopf and French (FW) were the first to obtain the correct result for the Lamb shift and the anomalous magnetic moment of the electron. At first FW results did not agree with the incorrect but independent results of Feynman and Schwinger (Schweber SS 1994 "QED and the men who made it: Dyson,Feynman,Schwinger and Tomonaga", Princeton :PUP). The 1963–1964 lectures Dirac gave on quantum field theory at Yeshiva University were published in 1966 as the Belfer Graduate School of Science, Monograph Series Number, 3. After having relocated to Florida in order to be near his elder daughter, Mary, Dirac spent his last fourteen years (of both life and physics research) at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Florida and Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida.

In the 1950s in his search for a better QED, Paul Dirac developed the Hamiltonian theory of constraints (Canad J Math 1950 vol 2, 129; 1951 vol 3, 1) based on lectures that he delivered at the 1949 International Mathematical Congress in Canada. Dirac (1951 “The Hamiltonian Form of Field Dynamics” Canad Jour Math, vol 3 ,1) had also solved the problem of putting the Tomonaga-Schwinger equation into the Schrödinger representation (See Phillips R J N 1987 “Tributes to Dirac” p31 London:Adam Hilger) and given explicit expressions for the scalar meson field (spin zero pion or pseudoscalar meson), the vector meson field (spin one rho meson), and the electromagnetic field (spin one massless boson, photon).

The Hamiltonian of constrained systems is one of Dirac’s many masterpieces. It is a powerful generalization of Hamiltonian theory that remains valid for curved spacetime. The equations for the Hamiltonian involve only six degrees of freedom described by  ,

, for each point of the surface on which the state is considered. The

for each point of the surface on which the state is considered. The  (m = 0,1,2,3) appear in the theory only through the variables

(m = 0,1,2,3) appear in the theory only through the variables  ,

,  which occur as arbitrary coefficients in the equations of motion. H=∫

which occur as arbitrary coefficients in the equations of motion. H=∫ x[

x[

–

–  /

/

] There are four constraints or weak equations for each point of the surface

] There are four constraints or weak equations for each point of the surface  = constant. Three of them

= constant. Three of them  form the four vector density in the surface. The fourth

form the four vector density in the surface. The fourth  is a 3-dimensional scalar density in the surface

is a 3-dimensional scalar density in the surface  ≈0;

≈0;  ≈0 (r=1,2,3)

≈0 (r=1,2,3)

In the late 1950s he applied the Hamiltonian methods he had developed to cast Einstein’s general relativity in Hamiltonian form (Proc Roy Soc 1958,A vol 246, 333,Phys Rev 1959,vol 114, 924) and to bring to a technical completion the quantization problem of gravitation and bring it also closer to the rest of physics according to Salam and DeWitt. In 1959 also he gave an invited talk on "Energy of the Gravitational Field" at the New York Meeting of the American Physical Society later published in 1959 Phys Rev Lett 2, 368. In 1964 he published his “Lectures on Quantum Mechanics” (London:Academic) which deals with constrained dynamics of nonlinear dynamical systems including quantization of curved spacetime. He also published a paper entitled “Quantization of the Gravitational Field” in 1967 ICTP/IAEA Trieste Symposium on Contemporary Physics.

If one considers waves moving in the direction  resolved into the corresponding Fourier components (r,s = 1,2,3), the variables in the degrees of freedom 13,23,33 are affected by the changes in the coordinate system whereas those in the degrees of freedom 12, (11-22) remain invariant under such changes. The expression for the energy splits up into terms each associated with one of these six degrees of freedom without any cross terms associated with two of them. The degrees of freedom 13, 23, 33 do not appear at all in the expression for energy of gravitational waves in the direction

resolved into the corresponding Fourier components (r,s = 1,2,3), the variables in the degrees of freedom 13,23,33 are affected by the changes in the coordinate system whereas those in the degrees of freedom 12, (11-22) remain invariant under such changes. The expression for the energy splits up into terms each associated with one of these six degrees of freedom without any cross terms associated with two of them. The degrees of freedom 13, 23, 33 do not appear at all in the expression for energy of gravitational waves in the direction  . The two degrees of freedom 12, (11-22) contribute a positive definite amount of such a form to represent the energy of gravitational waves. These two degrees of freedom correspond in the language of quantum theory , to the gravitational photons (gravitons) with spin +2 or -2 in their direction of motion. The degrees of freedom (11+22) gives rise to the Newtonian potential energy term showing the gravitational force between the two positive mass is attractive and the self energy of every mass is negative.

. The two degrees of freedom 12, (11-22) contribute a positive definite amount of such a form to represent the energy of gravitational waves. These two degrees of freedom correspond in the language of quantum theory , to the gravitational photons (gravitons) with spin +2 or -2 in their direction of motion. The degrees of freedom (11+22) gives rise to the Newtonian potential energy term showing the gravitational force between the two positive mass is attractive and the self energy of every mass is negative.

Amongst his many students was John Polkinghorne, who recalls that Dirac "was once asked what was his fundamental belief. He strode to a blackboard and wrote that the laws of nature should be expressed in beautiful equations."[30]

Personal life

Family

Dirac married Eugene Wigner's sister, Margit, in 1937. He adopted Margit's two children, Judith and Gabriel. Paul and Margit Dirac had two children together, both daughters, Mary Elizabeth and Florence Monica.

Margit, known as Manci, visited her brother in 1934 in Princeton from her native Hungary and, while at dinner at the Annex Restaurant (1930s–2006),[31] met the "lonely-looking man at the next table." This account came from a physicist from Korea who met and was influenced by Dirac, Y.S. Kim, who has also written: "It is quite fortunate for the physics community that Manci took good care of our respected Paul A.M. Dirac. Dirac published eleven papers during the period 1939–46.... Dirac was able to maintain his normal research productivity only because Manci was in charge of everything else."[32]

A reviewer of the 2009 biography writes: "Dirac blamed his [emotional] frailties on his father, a Swiss immigrant who bullied his wife, chivvied his children and insisted Paul spoke only French at home, even though the Diracs lived in Bristol. 'I never knew love or affection when I was a child,' Dirac once said." She also writes that "[t]he problem lay with his genes. Both father and son had autism, to differing degrees. Hence the Nobel winner's reticence, literal-mindedness, rigid patterns of behaviour and self-centredness. [Quoting the biography:] 'Dirac's traits as a person with autism were crucial to his success as a theoretical physicist: his ability to order information about mathematics and physics in a systematic way, his visual imagination, his self-centredness, his concentration and determination.'"[33]

Personality

Dirac was known among his colleagues for his precise and taciturn nature. His colleagues in Cambridge jokingly defined a unit of a dirac which was one word per hour.[34] When Niels Bohr complained that he did not know how to finish a sentence in a scientific article he was writing, Dirac replied, "I was taught at school never to start a sentence without knowing the end of it."[35] He criticized the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer's interest in poetry: "The aim of science is to make difficult things understandable in a simpler way; the aim of poetry is to state simple things in an incomprehensible way. The two are incompatible."[36]

Dirac himself wrote in his diary during his postgraduate years that he concentrated solely on his research, and only stopped on Sunday, when he took long strolls alone.

An anecdote recounted in a review of the 2009 biography tells of Werner Heisenberg and Dirac sailing on a cruise ship to a conference in Japan in August 1929. "Both still in their twenties, and unmarried, they made an odd couple. Heisenberg was a ladies' man who constantly flirted and danced, while Dirac—'an Edwardian geek', as [biographer] Graham Farmelo puts it—suffered agonies if forced into any kind of socialising or small talk. 'Why do you dance?' Dirac asked his companion. 'When there are nice girls, it is a pleasure,' Heisenberg replied. Dirac pondered this notion, then blurted out: 'But, Heisenberg, how do you know beforehand that the girls are nice?'"[33]

According to a story told in different versions, a friend or student visited Dirac, not knowing of his marriage. Noticing the visitor's surprise at seeing an attractive woman in the house, Dirac said, "This is... this is Wigner's sister". Margit Dirac told both George Gamow and Anton Capri in the 1960s that her husband had actually said, "Allow me to present Wigner's sister, who is now my wife."[37][38]

Another story told of Dirac is that when he first met the young Richard Feynman at a conference, he said after a long silence "I have an equation. Do you have one too?".[39]

Dirac was also noted for his personal modesty. He called the equation for the time evolution of a quantum-mechanical operator, which he was the first to write down, the "Heisenberg equation of motion". Most physicists speak of Fermi-Dirac statistics for half-integer-spin particles and Bose-Einstein statistics for integer-spin particles. While lecturing later in life, Dirac always insisted on calling the former "Fermi statistics". He referred to the latter as "Einstein statistics" for reasons, he explained, of "symmetry".

Religious views

Heisenberg recollected a conversation among young participants at the 1927 Solvay Conference about Einstein and Planck's views on religion. Wolfgang Pauli, Heisenberg and Dirac took part in it. Dirac's contribution was a criticism of the political purpose of religion, which was much appreciated for its lucidity by Bohr when Heisenberg reported it to him later. Among other things, Dirac said:

| “ | I cannot understand why we idle discussing religion. If we are honest—and scientists have to be—we must admit that religion is a jumble of false assertions, with no basis in reality. The very idea of God is a product of the human imagination. It is quite understandable why primitive people, who were so much more exposed to the overpowering forces of nature than we are today, should have personified these forces in fear and trembling. But nowadays, when we understand so many natural processes, we have no need for such solutions. I can't for the life of me see how the postulate of an Almighty God helps us in any way. What I do see is that this assumption leads to such unproductive questions as why God allows so much misery and injustice, the exploitation of the poor by the rich and all the other horrors He might have prevented. If religion is still being taught, it is by no means because its ideas still convince us, but simply because some of us want to keep the lower classes quiet. Quiet people are much easier to govern than clamorous and dissatisfied ones. They are also much easier to exploit. Religion is a kind of opium that allows a nation to lull itself into wishful dreams and so forget the injustices that are being perpetrated against the people. Hence the close alliance between those two great political forces, the State and the Church. Both need the illusion that a kindly God rewards—in heaven if not on earth—all those who have not risen up against injustice, who have done their duty quietly and uncomplainingly. That is precisely why the honest assertion that God is a mere product of the human imagination is branded as the worst of all mortal sins.[40] | ” |

Heisenberg's view was tolerant. Pauli, raised as a Catholic, had kept silent after some initial remarks, but when finally he was asked for his opinion, said: "Well, our friend Dirac has got a religion and its guiding principle is 'There is no God and Paul Dirac is His prophet.'" Everybody, including Dirac, burst into laughter.[41]

He may have reversed his views of God later, as this quote from May 1963's Scientific American suggests: "It seems to be one of the fundamental features of nature that fundamental physical laws are described in terms of a mathematical theory of great beauty and power, needing quite a high standard of mathematics for one to understand it. You may wonder: Why is nature constructed along these lines? One can only answer that our present knowledge seems to show that nature is so constructed. We simply have to accept it. One could perhaps describe the situation by saying that God is a mathematician of a very high order, and He used very advanced mathematics in constructing the universe. Our feeble attempts at mathematics enable us to understand a bit of the universe, and as we proceed to develop higher and higher mathematics we can hope to understand the universe better."

Death and commemoration

In 1984, Dirac died in Tallahassee, Florida and was buried at Tallahassee's Roselawn Cemetery.[42][43] Dirac's childhood home in Bristol is commemorated with a blue plaque and the nearby Dirac Road is named in recognition of his links with the city. A plaque on the wall at the Bishop Road Primary School shows the Dirac equation.[44] A commemorative stone was erected in a garden Saint-Maurice, Switzerland, the town of origin of his father's family, on 1 August 1991. On 13 November 1995 a commemorative marker, made from Burlington green slate and inscribed with the Dirac equation, was unveiled in Westminster Abbey.[42][45] Objections by the Dean of Westminster, Edward Carpenter, that Dirac was an atheist were brushed aside.[46]

Dirac shared the 1933 Nobel Prize for physics with Erwin Schrödinger "for the discovery of new productive forms of atomic theory."[1] Dirac was also awarded the Royal Medal in 1939 and both the Copley Medal and the Max Planck medal in 1952. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1930, an Honorary Fellow of the American Physical Society in 1948, and an Honorary Fellow of the Institute of Physics, London in 1971. Dirac became a member of the Order of Merit, an outstanding recognition by the land of his birth, in 1973. He had previously turned down a knighthood, as he did not want to be addressed by his first name.[47]

In 1975, Dirac gave a series of five lectures at the University of New South Wales which were subsequently published as a book, Directions of Physics (1978). He donated the royalties from this book to the university for the establishment of the Dirac Lecture Series. The Silver Dirac Medal for the Advancement of Theoretical Physics is awarded by the University of New South Wales on the occasion of the lecture.[48]

Immediately after his death, two organisations of professional physicists established annual awards in Dirac's memory. The Institute of Physics, the United Kingdom's professional body for physicists, awards the Paul Dirac Medal and Prize for "outstanding contributions to theoretical (including mathematical and computational) physics".[49] The first three recipients were Stephen Hawking (1987), John Stewart Bell (1988), and Roger Penrose (1989). The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) awards the Dirac Medal of the ICTP each year on Dirac's birthday (8 August). Also, the Dirac Prize is awarded by the International Centre for Theoretical Physics in his memory. Dirac House in Bristol is the headquarters of Institute of Physics Publishing.

The Dirac-Hellmann Award at Florida State University was endowed by Dr Bruce P. Hellmann (Dirac's last doctoral student) in 1997 to reward outstanding work in theoretical physics by FSU researchers.[50] The Paul A.M. Dirac Science Library at Florida State University, which Manci opened in December 1989, is named in his honour, and his papers are held there. Outside is a statue of him by Gabriella Bollobás.[51] The street on which the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory in Tallahassee, Florida, is located was named Paul Dirac Drive. As well as in his home town of Bristol, UK, there is also a road named after him in Didcot Oxfordshire, Dirac Way. The BBC named its video codec Dirac in his honour.

Legacy

Dirac is widely regarded as one of the world's greatest physicists. He was one of the founders of quantum mechanics and quantum electrodynamics.

His early contributions include the modern operator calculus for quantum mechanics, which he called transformation theory, and an early version of the path integral.[52] He formulated a many-body formalism for quantum mechanics which allowed each particle to have its own proper time.

His relativistic wave equation for the electron was the first successful attack on the problem of relativistic quantum mechanics. Dirac founded quantum field theory with his reinterpretation of the Dirac equation as a many-body equation, which predicted the existence of antimatter and matter–antimatter annihilation. He was the first to formulate quantum electrodynamics, although he could not calculate arbitrary quantities because the short distance limit requires renormalization.

In an attempt to solve the quantum divergence problem, Dirac gave a classical point particle theory combining advanced and retarded waves to eliminate the classical electron self-energy. Although these classical methods did not immediately solve the problems in quantum electrodynamics, they did lead John Archibald Wheeler and Richard Feynman to formulate an alternative Green's function description for light, which eventually led to Feynman's point particle formulation of quantum field theory.

Dirac discovered the magnetic monopole solutions, the first topological configuration in physics, and used them to give the modern explanation of charge quantization. He developed constrained quantization in the 1960s, identifying the general quantum rules for arbitrary classical systems.

Dirac's quantum-field analysis of the vibrations of a membrane, in the early 1960s, proved extremely useful to modern practitioners of superstring theory and its closely related successor, M-Theory.[53]

Bibliography

- Principles of Quantum Mechanics (1930): This book summarizes the ideas of quantum mechanics using the modern formalism that was largely developed by Dirac himself. Towards the end of the book, he also discusses the relativistic theory of the electron (the Dirac equation), which was also pioneered by him. This work does not refer to any other writings then available on quantum mechanics.

- Lectures on Quantum Mechanics (1966): Much of this book deals with quantum mechanics in curved space-time.

- Lectures on Quantum Field Theory (1966): This book lays down the foundations of quantum field theory using the Hamiltonian formalism.

- Spinors in Hilbert Space (1974): This book based on lectures given in 1969 at the University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida, USA, deals with the basic aspects of spinors starting with a real Hilbert space formalism. Dirac concludes with the prophetic words "We have boson variables appearing automatically in a theory that starts with only fermion variables, provided the number of fermion variables is infinite. There must be such boson variables connected with electrons..."

- General Theory of Relativity (1975): This 68-page work summarizes Einstein's general theory of relativity.

See also

- Dirac comb

- Dirac delta function,

- Dirac large numbers hypothesis

- Dirac notation

- Dirac matrices

- Dirac Prize

- Negative probability

Notes

- ^ a b "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1933". The Nobel Foundation. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1933/. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- ^ Farmelo 2009, p. 10

- ^ Farmelo 2009, pp. 18–19

- ^ Kragh 1990, p. 1

- ^ Farmelo 2009, pp. 10–11

- ^ Farmelo 2009, pp. 77–78

- ^ Farmelo 2009, p. 79

- ^ Farmelo 2009, p. 34

- ^ Farmelo 2009, p. 22

- ^ Mehra 1972, p. 17

- ^ Kragh 1990, p. 2

- ^ Farmelo 2009, pp. 13–17

- ^ Farmelo 2009, pp. 20–21

- ^ a b Mehra 1972, p. 18

- ^ Farmelo 2009, p. 23

- ^ Farmelo 2009, p. 28

- ^ Farmelo 2009, pp. 46–47

- ^ Farmelo 2009, pp. 52–53

- ^ Reminiscences about a great physicist, 1990 ed. Kursunoglu & Wigner, CUP,p.98

- ^ Dirac, P. A. M. (1928-02-01). "The Quantum Theory of the Electron". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character 117 (778): 610–624. Bibcode 1928RSPSA.117..610D. doi:10.1098/rspa.1928.0023.

- ^ Dirac, Paul A. M. (1933-12-12). "Theory of Electrons and Positrons". The Nobel Foundation. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1933/dirac-lecture.html. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ^ P. A. M. Dirac (1939). "A New Notation for Quantum Mechanics". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 35 (03): 416. Bibcode 1939PCPS...35..416D. doi:10.1017/S0305004100021162.

- ^ Gieres (2000). "Mathematical surprises and Dirac's formalism in quantum mechanics". Reports on Progress in Physics 63 (12): 1893. arXiv:quant-ph/9907069. Bibcode 2000RPPh...63.1893G. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/63/12/201.

- ^ P. B. Price; E. K. Shirk; W. Z. Osborne; L. S. Pinsky (1975-08-25). "Evidence for Detection of a Moving Magnetic Monopole". Physical Review Letters (American Physical Society) 35 (8): 487–490. Bibcode 1975PhRvL..35..487P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.35.487.

- ^ Blas Cabrera (1982-05-17). "First Results from a Superconductive Detector for Moving Magnetic Monopoles". Physical Review Letters (American Physical Society) 48 (20): 1378–1381. Bibcode 1982PhRvL..48.1378C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.48.1378.

- ^ "Magnetic Monopoles Detected In A Real Magnet For The First Time". Science Daily. 2009-09-04. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/09/090903163725.htm. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

- ^ D.J.P. Morris, D.A. Tennant, S.A. Grigera, B. Klemke, C. Castelnovo, R. Moessner, C. Czter-nasty, M. Meissner, K.C. Rule, J.-U. Hoffmann, K. Kiefer, S. Gerischer, D. Slobinsky, and R.S. Perry (2009-09-03). "Dirac Strings and Magnetic Monopoles in Spin Ice Dy2Ti2O7". Science (Science) 326 (5951): 411. Bibcode 2009Sci...326..411M. doi:10.1126/science.1178868. PMID 19729617.

- ^ S. T. Bramwell, S. R. Giblin, S. Calder, R. Aldus, D. Prabhakaran & T. Fennell (2009-10-15). "Measurement of the charge and current of magnetic monopoles in spin ice". Nature 461 (7266): 956. Bibcode 2009Natur.461..956B. doi:10.1038/nature08500. PMID 19829376.

- ^ Kragh 1990, p. 184

- ^ John Polkinghorne. 'Belief in God in an Age of Science' p2

- ^ "Last call at The Annex: Nassau Street institution closes doors after more than 70 years" by Sophia Ahern Dwosh with reporting by Euphemia Mu, The Daily Princetonian, 10 March 2006. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ^ "Wigner's Sisters" by Y. S. Kim, Department of Physics, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, U.S.A.; written in 1995, article in Web site dedicated to Paul A. M. Dirac. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ^ a b "Anti-matter and madness: British physicist Paul Dirac had a brilliant mind, but the joys of daily life flummoxed him" Review of The Strangest Man by Graham Farmelo by Robin McKie, The Observer, 1 Feb. 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ^ Farmelo 2009, p. 89

- ^ "Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac". University of St. Andrews. http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/Printonly/Dirac.html. Retrieved 24 November 2007.

- ^ Kragh 1990, p. 258 citing Mehra 1972, pp. 17–59

- ^ Gamow 1955, p. 121

- ^ Capri 2007, p. 148

- ^ Zee 2010, p. 105

- ^ Heisenberg 1971, pp. 85–86

- ^ Heisenberg 1971, p. 87

- ^ a b this web site "Dirac takes his place next to Isaac Newton". Florida State University. http://www.fsu.edu/~fstime/FS-Times/Volume1/Issue1/Dirac.html this web site. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac at Find a Grave

- ^ Al-Khalili, Professor Jim (28 Mar 2011 21h). "Four". UK: BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b00zwndy/Everything_and_Nothing_Nothing/. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ "Paul Dirac". Gisela Dirac. http://www.dirac.ch/PaulDirac.html. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Farmelo 2009, pp. 414–15

- ^ Farmelo 2009, pp. 403–404

- ^ "Public Dirac Lecture 2008". University of New South Wales. http://www.phys.unsw.edu.au/phys_news/Dirac.htm. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- ^ "The Dirac Medal of the Institute of Physics". Institute of Physics. http://www.iop.org/activity/awards/Premier_Awards/The_Dirac_Medal_and_Prize/page_1731.html. Retrieved 24 November 2007.

- ^ "Dirac Science Library". Florida State University. http://www.lib.fsu.edu/about/fsulibraries/dirac/. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Farmelo 2009, p. 417

- ^ Dirac, P. A. M. (1933). "The Lagrangian in Quantum Mechanics". Physikalische Zeitschrift der Sowjetunion 3: 64–72.

- ^ Britain's answer to Einstein [1]

References

- Capri, Anton Z. (2007). Quips, Quotes, and Quanta: An Anecdotal History of Physics. Hackensack, New Jersey: World Scientific. ISBN 981-270-919-3. OCLC 214286147. http://books.google.com/?id=GfmR0mHxeZkC&pg=PA148. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- Crease, Robert P.; Mann, Charles C. (1986). The Second Creation: Makers of the Revolution in Twentieth Century Physics. New York, New York: Macmillan Publishing. ISBN 0025214403. OCLC 13008048.

- Farmelo, Graham (2009). The Strangest Man: the Life of Paul Dirac. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0465018270. OCLC 426938310.

- Gamow, George (1985). Thirty Years That Shook Physics: The Story of Quantum Theory. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-486-24895-X. OCLC 11970045. http://books.google.com/?id=L90_wY1VCW0C&pg=PA121. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- Heisenberg, Werner (1971). Physics and Beyond: Encounters and Conversations. New York, New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0061316229. OCLC 115992.

- Kragh, Helge (1990). Dirac: A Scientific Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38089-8-1. OCLC 20013981. http://books.google.com/?id=5ajhJGdL0J4C&pg=PA184. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- Mehra, Jagdish (1972). "The Golden Age of Theoretical Physics: P. A. M. Dirac's Scientific Works from 1924–1933". In Wigner, Eugene Paul; Salam, Abdus. Aspects of Quantum Theory. Cambridge: University Press. pp. 17–59. ISBN 0521086000. OCLC 532357.

- Schweber, Silvan S. (1994). QED and the men who made it: Dyson, Feynman, Schwinger, and Tomonaga. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691036853. OCLC 28966591.

- Zee, A. (2010). Quantum Field Theory in a Nutshell. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400835324. OCLC 318585662.

Further reading

- Brown, Helen (24 January 2009). "The Strangest Man: The Hidden Life of Paul Dirac by Graham Farmelo – review [print version: The man behind the maths]". The Daily Telegraph (Review): p. 20. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/bookreviews/4316309/The-Strangest-Man-the-Hidden-Life-of-Paul-Dirac-by-Graham-Farmelo---review.html. Retrieved 11 April 2011..

- Gilder, Louisa (13 September 2009). "Quantum Leap – Review of 'The Strangest Man: The Hidden Life of Paul Dirac by Graham Farmelo'". The New York Times (Review). http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/13/books/review/Gilder-t.html?scp=1&sq=dirac&st=cse. Retrieved 11 April 2011..

Dirac videos

External links

- Dirac Medal of the International Centre for Theoretical Physics

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Paul Dirac", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Dirac.html.

- Dirac Medal of the World Association of Theoretical and Computational Chemists (WATOC)

- The Paul Dirac Collection at Florida State University

- The Paul A. M. Dirac Collection Finding Aid at Florida State University

- Photocopies of Dirac's papers from the Florida State University collection, held under Dirac's name in the Archive Centre of Churchill College, Cambridge, UK

- Letters from Dirac (1932–36) and other papers, held in the Personal Papers archives of St John's College, Cambridge, UK

- Free online access to Dirac's classic 1920s papers from Royal Society's Proceedings A

- Annotated bibliography for Paul Dirac from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Oral History interview transcript with Paul Dirac 1 April 1962, 6, 7, 10, & 14 May 1963, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives

- Photos of Paul Dirac at the Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, American Institute of Physics

- 2010 June 24 – ScienceTalk Part 1 of interview with Graham Farmelo author of The Strangest Man of Science

- 2010 June 24 – ScienceTalk Part 2 of interview with Graham Farmelo author of The Strangest Man of Science

|

||||||||

|

|||||